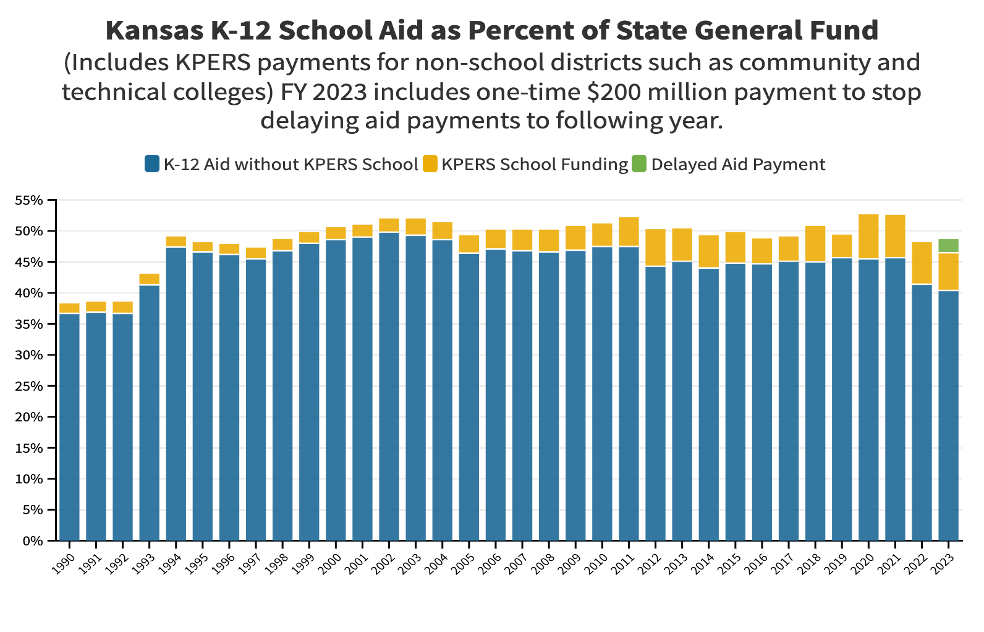

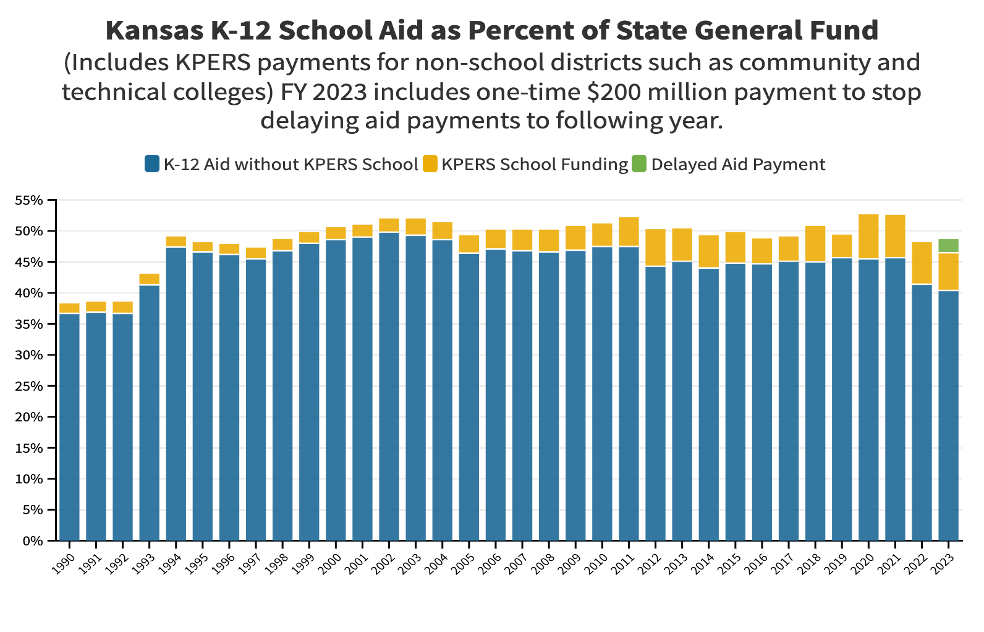

Despite increasing school funding in response to the Gannon school finance case, the share of the state general fund budget going to K-12 aid dropped below 50 percent last school year and is expected to be below 50 percent for the upcoming school year 2022-23.

While there have been concerns that K-12 funding is taking over an ever-larger share of the state budget, in fact, the percentage of the SGF going to K-12 state aid is projected to be at its lowest in over two decades, according to the recently released Comparison Report on the state budget prepared by the Kansas Budget Division.

The report shows the Kansas Legislature appropriated aid and other assistance for elementary and secondary education of $4.109 billion last fiscal year (ending in June 2022) from the state general fund. That was 48.3 percent of total general fund appropriations of $8.513 billion.

For the current fiscal year, July 1, 2022, to June 30, 2023, the Legislature appropriated $4.463 billion for K-12 aid, or 48.7 percent of total SGF appropriations of $9.169 billion.

The school district state aid now is the smallest share of the state general fund since the late 1990s.

Why this matters:

For years, some legislators and others have suggested that school district aid is taking a growing share of the state budget, squeezing out funding for other programs and growing at an "unsustainable" rate. However, school aid has accounted for about 50 percent of the state general fund budget since the mid-1990s, when the Legislature increased state aid in part to reduce local property taxes.

Kansas continues to provide a larger share of school funding from state aid than most states but also relies less on local funding sources, which are mostly property taxes.

Since the Gannon funding phase-in began in 2018, the state general fund has increased by nearly $2.9 billion. Of that amount $1.5 billion was K-12 state and $1.5 billion was for all spending, based on funding appropriated through the 2022 Legislature.

Understanding the school district delayed aid payment.

The current year's total school district aid includes almost $200 million in additional school funding to end the practice of delaying a portion of state aid until the next fiscal year. Without this extra funding for the delayed payment, K-12 aid would be just 46.5 percent of the state general fund.

Since 2003, a portion of the final general state aid and local option budget aid payment due to school districts in June has not been paid until July. This has allowed the state to reduce its spending for a given year without appearing to reduce school aid. Districts, however, are required to account for the funding as though it was received in June.

Why this matters:

Funding for delayed payments in 2023 does not give school districts additional spending power. State aid will be reduced by the same amount the following year, which will also have no impact on actual spending by districts.

Counting the delayed payments means school finance aid is increasing $400 million this year, or over 8 percent. However, an increase that will make a difference in school districts spending is only $200 million, or less than the projected rate of inflation.

Changes in KPERS aid.

K-12 aid jumped to over 52.6 percent of the state general fund in 2020 and 2021. However, a significant reason was not increased funding for school finance programs under Gannon. Rather, the Legislature has been increasing the rate of contributions to the underfunded KPERS retirement system. Payments to school districts for KPERS more than doubled from $253 million in 2017 to over $580 million this year. In 2000, KPERS school payments amounted to 2 percent of the state general fund but have increased to about 7 percent now.

Why this matters:

Increasing KPERS contributions has been necessary to sustain retirement benefits for school and other public employees in Kansas. The system became badly unfunded over recent decades when the Legislature did not make contributions at the actuarially required level. To compensate for those shortfalls, the state is making much higher contributions now.

Those contributions show up as K-12 state aid and in school district budgets, but it is important to note that those contributions do not increase how much school districts actually have to spend. The money simply passes through district budgets on its way to KPERS fund. The state should certainly get credit for KPERS school funding – all of those contributions eventually go to district employees as retirement benefits. But the increased KPERS funding does not give school districts additional spending on their operating costs, such as teacher salaries, energy costs, etc.

Likewise, reductions in KPERS contributions do not affect district spending power. The 2022 Legislature voted to pay off some previously scheduled KPERS payments early. As a result, KPERS school aid will be almost $25 million lower this year than last year, but that change doesn't affect school district spending power; it just means the money they will send on to KPERS will be less.

Additional settings for Safari Browser.

Additional settings for Safari Browser.