Getting more students to complete some kind of educational credential after high school is perhaps the top goal of the State Board of Education’s Kansans Can education vision, because postsecondary education is so closely tied to economic security. Over the past several decades, it has become increasingly difficult to have a “middle class” life without more than a high school diploma.

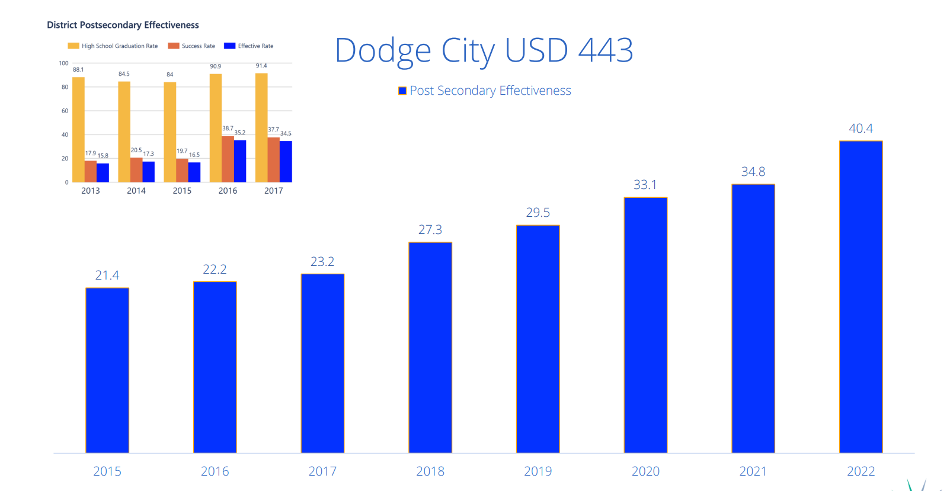

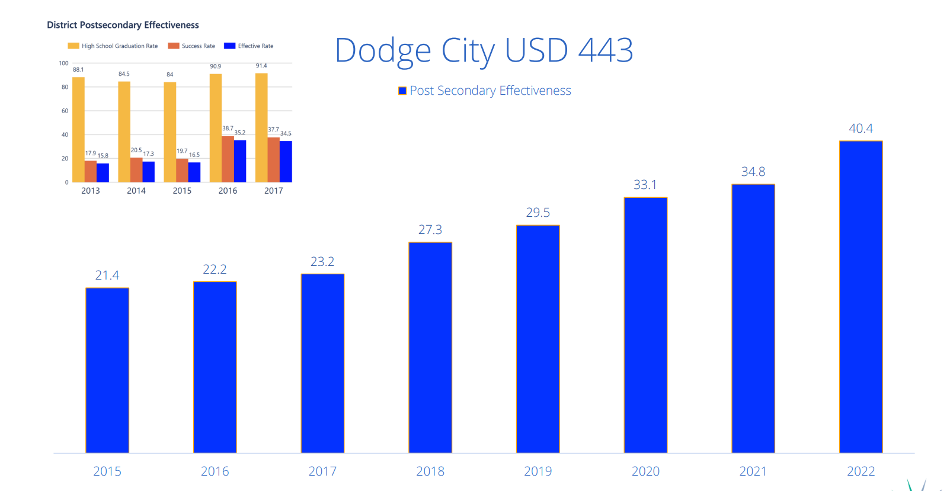

When Education Commissioner Randy Watson shared with the State Board in August that Dodge City USD 443 has nearly doubled its postsecondary effective rate – the percent of a graduating class that completes high school in four years and have either completed or is enrolled in a postsecondary program within the next two years – it drew attention for many reasons.

It was a dramatic increase over a period when the state as a whole has been improving, but much more slowly, and it was sustained over the COVID pandemic when statewide postsecondary enrollment dropped.

Dodge City – a plaintiff district in both the recent Gannon school finance lawsuit and the previous Montoy lawsuit – is a district that seems to have a lot stacked against it, starting with one of the highest poverty rates in the state (nearly 80% of students on free or reduced-price meals). Its student population is 85 percent non-white; mostly Hispanic with a large number of recent immigrants. Nearly half of its students are English Language Learners and go home to a family that speaks another language there. About 400 students each year are new to U.S. schools, many having years of interruption in whatever schooling they’ve received.

Many of these students would be the first generation in their families to have any postsecondary education so would lack experience in navigating college application, funding and completion. In fact, for many a job in the beef packing industry in the area is a ticket to the highest standard of living they have ever known.

I wanted to find out how Dodge City has been having success despite these challenges, so I spent a morning with high school staff, district and community leaders. I learned a lot about programs and strategies the district credits for its success, and how increased state funding has expanded what can be done. They also say some of it has been luck or timing: the right people coming together at the right time. They admit great challenges remain.

But what struck me most from the nearly 20 leaders I met with was a belief that they CAN help students do better. A frequent phase was “intentional;” that the district has set out to do things differently to get different results and is committed to careful monitoring of progress and adjustment. Finally, there was a passionate expression that the school system must be advocates for their students, to help them find their strengths, set higher expectations and prepare for a better future.

Many of the district’s leaders are relatively new to their positions, and while a number of the efforts under way are not new to Kansas education, they were new to Dodge City. The district’s current efforts began with an academic audit requested when Superintendent Fred Dierksen arrived six years ago, leading to a wide range of efforts to improve learning and better prepare students for success after high school.

“We didn’t lay out a plan to bring our postsecondary success rate up,” said Dierksen, “but everything we are doing is designed to help kids be successful.”

Long-time school board member Ryan Ausmus said the board and the district have shifted to a greater focus on education results. “As a board member, at least my philosophy, we should be concentrated on two things. Safety, which in this day and age is of extreme importance, and the district has taken steps to reduce our risk as much as possible. And two, academic achievement. So, it has been a breath of fresh air that over the last couple of years at almost every board meeting, we have something tied into our agenda about academics, or student achievement or how we’re progressing on meeting an academic outcome. As a board member, that’s been really great to see.”

“Bringing people in, taking people out.”

In a round table discussion with high school leaders, Deputy Superintendent Scott Springston credited improved postsecondary results to three things: stronger business connections, partnerships with Dodge City Community College and increased state funding to add positions to support those efforts. As a plaintiff in the Gannon school finance case, Dodge City benefited not only from a higher base budget per pupil but from the increased funding for at-risk and bilingual weightings that came with a higher base. But in addition to funding, the district made a change in focus.

“We have had a mind shift that not everyone wants to go to a four-year institution, or has the means to go, or needs to go,” said Mike Martinez, Career Technical Education Director and Assistant Principal, who came on board four years ago. “We needed to home in on giving students the skills to go directly into the workforce, or transition to community college, or another path to purposeful life here in Dodge City. A majority of students will not leave Dodge City, so we need to give them skills for the business and industries in our area, to be successful here.”

With that goal, the district hired Maria Kane, a former employee of the local chamber of commerce. “Working with Maria and business connections, we focus on bringing people in and taking people out. Bringing speakers from employers into school to talk to students about opportunities and taking students to activities showing them what we have in the community, that it’s more just the plant where their parents might work,” said Martinez, referring to the meat packing plants that have been a draw for Hispanic immigration to the area.

Taviana Lowery, instructional coach, agrees. “Much of our success is immersing ourselves in what students want to do beyond Dodge City High School. Getting to know these students and trying to provide them with experiences and opportunities to be successful beyond high school.” Likewise, Heather Steiner, with 18 years as a teacher and instructional coach, said, “I saw many students not interested in traditional college courses, but they became interested in CTE connections like welding, especially among male students. They have been able to gain a certificate and experiences to help them after leaving school, without two-year or four-year degrees.”

A technical certificate in welding or any other Career Technical Education program counts just as much to the State Board’s postsecondary success measure as a two or four-year degree program. The Board’s vision is based on projections that about 75 percent Kansas jobs going forward will require a postsecondary credential, about half of those require technical certificates and two-year degrees and half requiring a four-year degree or more.

To support that vision, one of the Kansans Can outcomes is for every student to have an individual plan of study, based on the student’s career interests. Starting five years ago, every student at Dodge City High School is enrolled in a career pathway based on their interests, which can change if their interests change. “That means, even as freshmen, students are looking at career areas and the academics that support their goals,” said Steiner. “Entry level courses are broad enough and short enough that students aren’t locked in. If they find out they don’t like it, they can try something else; if they like it, they can keep on that path.”

Each student has a flex or homeroom period, with the same teacher all four years. Flex teachers are the main connection to parents, helping students work on what they want to do. Speakers from community employers are brought in during flex time, and teachers can direct students to presentations based on their interests. Every Tuesday, business representatives are brought in, from all types of employers, military to healthcare. All career pathways are represented, from large international companies to local businesses. Thursdays focus on employability skills, such as how to deal with people, how to deal with a boss, how to find a job, or how to quit a job.

As pathways advisor, Kane helps connect students with business partners to learn about careers they would never know about if not for bringing people into building. In addition, the district hired a College Advisor, Kirsten Frink, to work one-on-one with students, helping them understand a postsecondary system their parents may not know about, and are aware of options like Excel in CTE and the new Kansas Promise Scholarship Program.

"We saw need to be more purposeful with seniors,” said Martha Mendoza, high school principal. “We put a team together to develop a checklist for what needs to be done month by month that senior year to prepare for graduation and beyond. We set up parents' nights to help with issues like filling out FAFSA (college financial aid form). We have a lot of first-generation college students, so we need to be more purposeful for their success.”

Other new efforts including adding the Jobs for America’s Graduates (JAG) program. This elective class provides academic and other supports to ensure students earn their diploma, explore career opportunities and practice soft skills to prepare for transition to post-secondary education, military service, or into the workforce following their graduation. The district also added a JROTC program, certifications in fire and police, and the Communities in Schools Program. “All of these programs are designed to expand horizons for our students.” said Superintendent Dierksen.

“I hope what you are hearing is that we are giving our kids hope and options,” said Melanie Scott, high school counselor. “Letting them know there are choices.” She credits the district for hiring people to focus on career and business connections; goals can’t be achieved as well by counselors focusing on other needs. Like taking students to job sites: hearing kids express interest in say, construction trades, but not knowing what really it means. They can go to ‘manufacturing day’ and their eyes light up with the new possibilities they have seen.”

Board member Ausmus noted a young family member who immigrated from Mexico last year took a school trip to Kansas State University. Before that experience, she had no idea what a college even was. “Coming from Mexico, the area from which she is from, going to a place like KSU is almost unimaginable. The beauty, the things she was able to witness on that tour, was through the efforts of USD 443. There are a lot of wonderful things going on to expose our students to things outside of the city limit, which is all they may have known.”

“Amazing synergy” in community

In addition to helping students tee more opportunities and understand the preparation needed, district leaders credit a close relationship with Dodge City Community College for expanding opportunities and helping DCCC to accommodate high school students.

Clayton Tatro, DCCC Vice President for Workforce Development, said he arrived in 2019 with a charge from the president to open up offerings to high students and increase the focus on technical education. Those goals grew out of joint planning between the school district, college, business and community leaders to better meet the community’s needs.

Tatro said he found the college somewhat “sleepy” in tech ed offerings, but quickly set about to change that in cooperation with high school leaders. "We said from the beginning we needed to open up all programs to high school students and we did. COVID was a setback, but our goal is to make college completely open to the high school. We’re not there yet, but pretty darn close.”

How were barriers removed? “It was the right person, right place, right time,” said Tatro. “I have been at Washburn Tech, where half of the students are in high school. Everyone is based on working with high schools, same schedule, teachers, grades, transcripts. We’ve been working to move that model to Dodge City.”

District leaders credit support from the college president, with a team of district leadership and community members working to build a seamless system. "Making connections is critical,” said Springston. “I’ve worked at a lot of places (that try to do that), but this is the best I’ve seen. Listening to students and parents, making home visits for parent-teacher conferences, using English Language support, going to people instead of making them come to us.”

Tatro agreed. “At a macro level: city, county, school, college have an amazing synergy. The leadership of those entities have flipped a switch to move the community ahead, working together extremely well. It must be intentional. Just being open isn't enough.”

Board member Ausmus, who previously worked at the college, noted it set a record for dual credit enrollment last year. That enrollment includes his daughter, a senior in high school who is taking dual enrollment nursing courses. “For us as a family, for her to be able to get a jump start on her education will allow her to finish all of her pre-requisites when she graduates high school and be able to enter nursing school almost immediately. Not to mention those courses are almost all free – so from a father’s perspective, it is a great opportunity.”

“The Dodge City area is growing, business is expanding, and we have 2.9% unemployment,” said pathway coordinator Kane. “If schools can’t develop students to meet those workforce needs, the community may lose those jobs. Businesses will pay for training; apprenticeships will pay for students to go to school. It’s not the old idea of getting financial aid, going to college, then looking for a job. It is a chance to go to work and school at the same time, right away.”

Kane also said the community came together to develop the Rural Education and Workforce Alliance. REWA was created to bring bachelor’s level degree programs to southwest Kansas, the only area of the state without a four-year college or university. For school district jobs that require a four-year degree, students can begin in an education pathway in high school, go to the community college for two years, then complete degree programs through REWA in coordination with higher education institutions.

Challenges and Opportunities

Second-year High School Principal Martha Mendoza immigrated to the U.S. as a child, grew up and went to school in Dodge City. A long-time educator in the system, she notes the wide variety of experiences among her students, who are overwhelmingly Hispanic.

"Some of our students have parents I taught myself,” she said. “Some students go home to Spanish language households. And for some students, we are the first ones to show them how to hold a pencil.” Classes may include “unaccompanied minors,” children usually aged 15-18 who are detained at the U.S. border without parents or other relatives. Such students are usually placed with next of kin as their immigration situation is resolved, and many come to Dodge City because of relatives working in beef packing plants. “Their goal in crossing the border is to work,” said Mendoza. “School is the last thing on their minds. They came to provide for their families, then find themselves in school because they must attend an educational program while in the country.”

Such students are often identified as “SLIFE” (Students with Limited or Interrupted Formal Education). These students may not have been in a classroom for years, let alone an American classroom. Last year, 40 students came to the district as juniors or seniors with zero credits; no chance to graduate on time. Often such students are only in the district for a year or two. Yet all counted for the district’s graduation rate, test scores and accountability.

Such students exemplify the challenges faced by a district like Dodge City, with high poverty rates, legal and undocumented immigration, language barriers and cultural differences, in trying to increase postsecondary success.

“Our biggest problem is the financial strain on families,” said instructional coach Taviana Lowery. “Families living paycheck to paycheck. Their focus is not on education but on survival. Many have left horrible situations behind. Getting here, getting a job at a packing plant is amazing, just being able to go to the store and buy food regularly. So, getting them to think about more, about living the whole American dream, is a big step.”

Mendoza agrees. “How can we overcome those issues, so they are not just living day to day? Getting students and parents to see beyond. How do we encourage students to dream big? If they do leave for a four-year college, how to we help them succeed? Because they likely will come home to this community due to strong ties to their family.”

Other district leaders, including Assistant Superintendent for Secondary Matt Turner, say the lack of understanding about education can contribute to such issues as chronic absenteeism, which exceeds 20 percent. “Too often families don’t understand the importance of attending school, and that any absence is a problem,” he said. “If a student misses just two days of school each month, that’s 18 days in a year. Over ten years, by 11th grade, that equals an entire school year of 180 days. It’s hard to be on grade level in high school if you have missed an entire year of school.”

Another challenge is the language barrier. “Half of our students go home to family where English isn’t spoken or isn’t the main language,” said Principal Mendoza. “That means there is no one to help students with schoolwork in English, to answer questions. In fact, we have many students where the home is trilingual, with mom and dad each speaking a different language and the child trying to learn English.”

Cultural ties also mean students with relatives in other counties often take an extended winter break from school, longer than the regular holiday break. This creates additional absences that can put the student farther behind. “We try to work with those families to say, if you’re going to do that break, it's all the, more important for kids to be in school the rest of the time,” said Turner. “We also try to work with others in the community, like doctors and dentists, to try to schedule appointments when school is not in session.”

But those same cultural issues that can be a challenge can also be an advantage. While many young Americans dream of leaving home for college and starting a family, cultural ties in the Dodge City community mean a desire to stay close to home and families. That means if Dodge City can give more students higher academic, technical and workforce skills, they are less likely to export them to other communities and states.

"This year, we have an abundance of students who want to be teachers,” said Mendoza, “and want to stay local. Over 30 are interested, and one of our teachers has taken them on as a special project, trying to find funding for these students to pursue education. If we can support them, it will help them and also help us address our teacher shortage issue,” which she notes is a persistent problem.

However, another barrier for some students is their undocumented immigration status, which many students may not even know about until late in their school career, having come to the United States as young children. Undocumented students can’t get into programs or professions that require a license without a social security number, and they can’t get federal financial aid to attend college. School leaders say it’s a bigger problem in more traditionally female areas such as education and nursing. Male students, who may be interested in areas like construction that don’t require the same level of licensing and education, are less effected.

Public schools are required to educate students, regardless of citizenship status under a U.S. Supreme Court ruling, so districts don’t know how many students are undocumented. Mendoza says when the federal government created the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, the district knew of about 120 Dodge City students who applied. The program is now in legal limbo in the federal court system. While DACA allows individuals to work, it does not allow financial aid. (Kansas allows certain undocumented students to pay in-state tuition at public universities, but that still leaves the cost beyond many students. The state’s new Promise Scholarship Act, which is designed to cover the cost of one- and two-year programs, now requires proof of citizenship to receive aid.)

“How do we motivate girls in class to stay in school and prepare for postsecondary education when they have seen an older sister face these barriers?” asked Mendoza. “Why not just get married and have babies right away if they see no other options?” She recalled a young man who told her, “In elementary school they encourage you to believe you can do anything. Then as you get older, you learn you can’t. You can’t drive, you can’t get a job, can’t go to college.” These students, she said, “feel like they are stuck.”

More to do

Although Dodge City has taken steps to increase student interest in and access to postsecondary education, leaders acknowledge that students also need the academic preparation to succeed in postsecondary studies.

Superintendent Dierksen said the district’s academic audit found that “We didn’t have organization in our curriculum. We didn’t have an organized process, so all buildings weren’t on the same page.” That has led to changes in classroom instruction.

“We need to make sure every classroom has the rigor, that we are teaching to the standards,” said Principal Mendoza. “That’s a challenge when we also having trouble finding teachers, substitutes.” She noted the school recently “lucked into several cases” of people with college backgrounds in biology and business who are now new teachers.

“Every year we hire about 70 people. About half of those people don’t have what you would call traditional teaching training.” said Deputy Superintendent Springston. “It doesn’t mean they don’t have the capability, but it means we have to support them differently. It means we need clarity, alignment, and very focused and integrated professional development. We need to make sure we are teaching the standards, not just teaching but showing that kids can demonstrate a depth of knowledge.”

Springston said state assessments, which are used by the State Board of Education as factor in school accreditation along with graduation rates and postsecondary success, are important as data points. “Teachers really need to use data to monitor how well students are doing. We have been placing emphasis at the early grades to prepare kids for high school, because by that point, there isn’t much time.”

“We’ve had a shift in focus in teaching ELA at high school,” said instructional coach Steiner, who is a former English teacher herself. “English teachers are content teachers. Our education was to teach literature. We have found we have to be reading teachers, as well, because of the deficits our kids come to us with and those gaps we need to fill. We’ve done a lot with professional development, we’ve had summer workshops to help teachers align their teaching and give them strategies to embed skills lower-level students need, like phonemic awareness. This summer, several teachers were trained in LETRS (Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling), geared to high school teachers to focus on teaching reading.”

The district is also working to help teachers to understand student issues. For example, math teachers who use word problems may see students struggling because they have reading issues, not math issues.

Finding the strengths in each student

All of the district’s leaders agreed that another shift in thinking was important: to look for each student’s strengths or advantages, not just their disadvantages.

Diana Mendoza, Director of English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) and Diversity, and recent appointee to the Kanas State Board of Regents, shared the story of a young man who travelled with a district team for a Dia De Los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, event at the State Capitol in Topeka. “We were standing in the lobby of the hotel, and this young man, an immigrant student, said ‘This is beautiful! Can you just leave me here? You can tell my aunt (who he was staying with) you lost me.’ And we looked at him and said, tell you what, if you can come up with a plan to survive here by yourself, we’ll consider leaving you here.”

“And he said ‘Oh, Miss! I walked all the way from Honduras. I can survive by myself!’ As we learned more about this young man, we first figured here he is in a SLIFE classroom with almost no education, and probably would have many people saying, ‘he can’t.’ But after graduation, we did a video with him, we learned he had been doing construction at eight years old, he knew how to find the circumference of things, he had all of these math skills that we never would have known if we hadn’t taken the time to get to know him. So maybe he couldn’t read and write in English, but he had a huge skill set to contribute.”

“We don’t realize where our students come from and what their background is and what they’ve been through, and the abilities they have,” said Superintendent Dierksen. “It’s unbelievable what these students can do if given a chance.”

Additional settings for Safari Browser.

Additional settings for Safari Browser.