As school boards work to effectively plan ways to improve student success, a common – and controversial – key data point is performance on state assessments.

Some say these assessments are the most important measure of student and district performance: an annual, objective measure of academic knowledge at six grade levels. The Legislature requires districts to provide public links to this information for accountability reports and use assessments results in budgeting. State assessments were also used by the plaintiffs in previous school finance lawsuits to argue that schools needed more funding – and that funding would improve student outcomes. Under this view, raising test scores should be the major focus of school board planning,

Others say test scores already receive too much emphasis: that test scores are a single snapshot that may not reflect how well a student is doing, and that other measures – not just academics – are equally or more important to a student’s long-term success.

New research by the Kansas State Department of Education indicates there is truth to both positions.

Doing well on the Kansas state assessments likely means a student is on track to graduate and then succeed in his or her postsecondary efforts. However, many students do better – and some do worse – in these outcomes than the test scores would predict, which indicates there are many variables when it comes to student success.

State assessments are one of the outcomes used by the State Board of Education for school accreditation and accountability and receive significant Legislative and public attention. The research suggests improving test results will increase student success but should not be used as the only measure of a student’s preparation.

State assessments are one measure of school and student success under the state’s education vision.

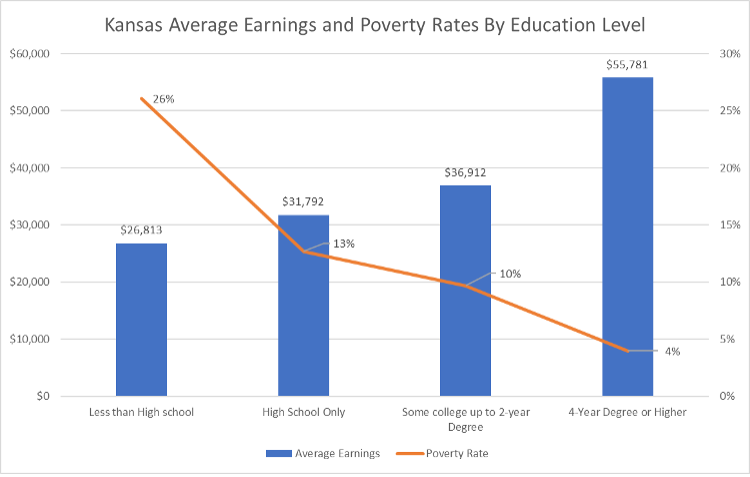

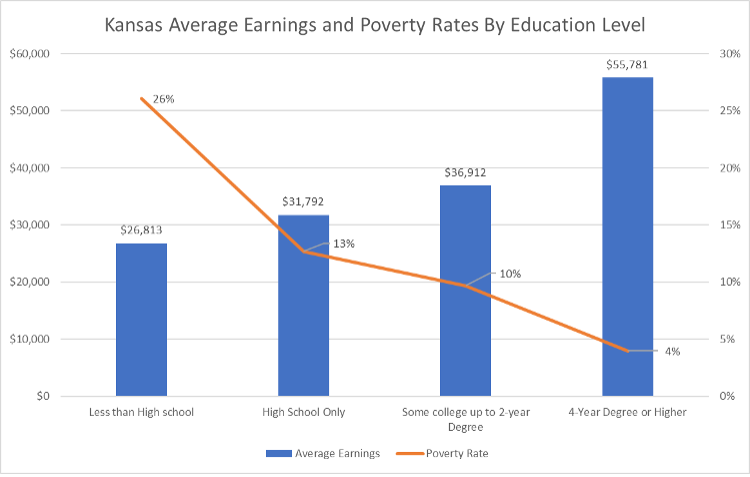

Under the State Board of Education’s Kansans Can vision, high school graduation and some type of postsecondary education will be important to a student’s future economic success, with about 90 percent of jobs expected to require at least a high school diploma and 75 percent of jobs expected to require a technical certificate, two-year degree, four-year degree or higher. Each increase in educational attainment, from high school completion to advanced degrees, results in higher earnings, higher employment rate and lower poverty rates on average.

The Board uses three "quantitative” outcomes for school accreditation and recognition programs: state English Language Arts (ELA) and math assessments measuring skills for postsecondary readiness; the graduation rate for students in four years; and postsecondary success – the percentage of students who have either completed a postsecondary credential (technical certificate or academic degree) or are enrolled in a postsecondary program within two years of graduation. State assessments given at grades 3-8 and 10 are also required by federal law.

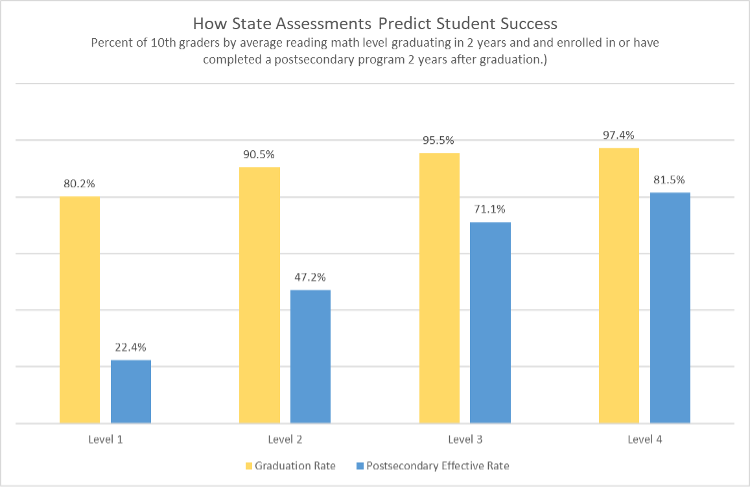

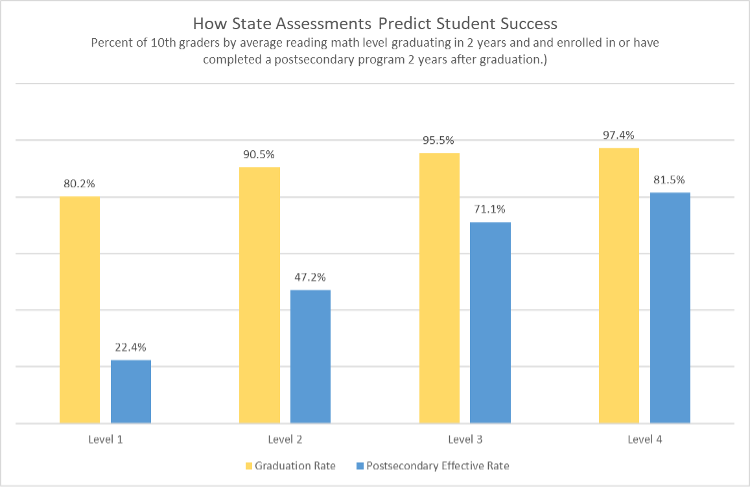

The new research shows that for each of the four levels where students are grouped on state assessments at grade 10, the percentage of students reaching higher outcomes increased at every level. That suggests that if districts increase the number of students at higher levels on state tests, graduation and post-secondary success rates will also improve.

The research: on average, higher test scores predict higher educational attainment

KSDE chose a sample of students who took the ELA and math tests in 10th grade, then looked at the results for students in each of the four assessment levels on the following:

Did the student take the ACT test as a junior or senior, which indicates an interest in postsecondary education?

Did the student score in the top half of students who take the ACT test for college readiness?

Did the student graduate high school at grade 12?

Did the student complete a postsecondary credential or was enrolled in a postsecondary program two years after graduation?

The following results average the percentage of students in reading and math meeting those benchmarks.

Level One. Less than half (45.6 percent) of students at Level One took the ACT and only 3.6 percent scored in the top half of the ACT. Just over 80 percent of Level One students graduated in four years. Of these graduates, 26.8 percent had completed a credential or were enrolled after two years (the postsecondary success rate). When multiplied by the graduation rate, that meant 22.4% of Level One students in that grade cohort had postsecondary completion or enrollment (the postsecondary effective rate).

Level Two. Over two-thirds (69.1 percent) of students at Level Two took the ACT and about one-quarter (24.6 percent) scored in the top half. The graduation rate for Level Two increased to 90.5 percent from 80 percent in Level One, and the postsecondary effective more than doubled to 47.2 percent. That means more than half of Level Two students DID NOT reach postsecondary success when facing a future that estimates about three-quarter of jobs – and a higher percentage of jobs paying “middle class” wages, will require more than high school.

Level Three. At Level Three, 86.7 percent of students took the ACT and 69 percent scored in the top half of the ACT. The graduation rate is just over the State Board goal of 95 percent, and the postsecondary effective rate of 71.1 percent is just under the goal of 75 percent.

Level Four. At the highest level, over 90 percent of students took the ACT and over 90 percent scored in the top half of the ACT; over 97 percent of students graduate on time; and over 80 percent have completed a postsecondary credential or remain enrolled two years after graduation.

These results indicate that state assessments generally do what they were designed to do: measure academic readiness for postsecondary success. With each higher level, students on average are more likely to graduate on time, be better prepared for college (as measured by the ACT) and are more likely to have earned or be on track for a postsecondary credential than the level below. The postsecondary effective rate doubles from Level One to Level Two, and triples from Level One to Level Three.

State assessment scores are not always predictive for individual students.

While students on average do have better results when they score higher on state assessments, many students in the lower two levels go on to graduation and postsecondary success. More than one in five of students in the lowest level DID go on to postsecondary success within two years, as did nearly half of students in Level Two. At the same time, nearly 30 percent of students at Level Three and 20 percent at Level 4 did not meet the definition of postsecondary success two years after high school.

Among the reasons: some students may test poorly on a given day due to other circumstances in their lives, or simply not take the tests seriously. They may have fallen behind when a test is given and catch up later. Particularly in high school, students may not have taken the course or been exposed to the material tested in tenth grade but can cover what they are missing by the time they graduate. As with all formal assessments, it’s wise to remember that they represent a “point in time.”

On the other hand, some students test well and have a good grasp of academic content but have other issues – social, emotional, physical or financial – that cause them to drop out of high school or postsecondary programs without finishing. Or high-scoring students may simply take a year or two off after school and are not counted for “postsecondary success” within two years, then successfully return to postsecondary programs later.

Some groups lag behind on assessments, educational attainment and economic status.

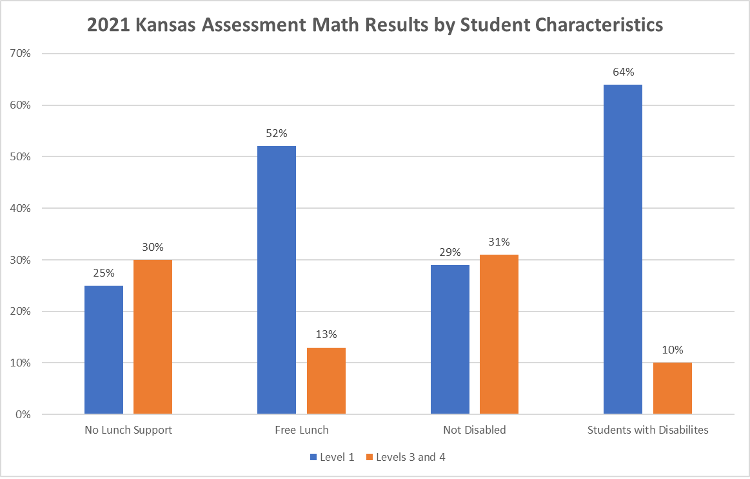

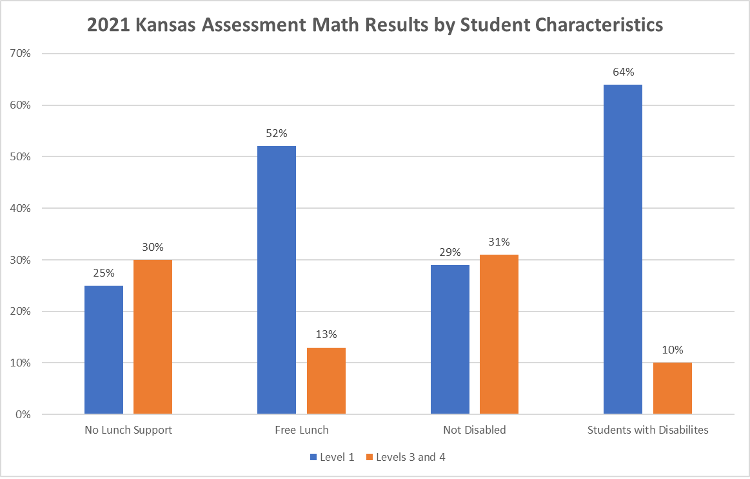

There are large differences in student performance based on student background and needs. For example, 52 percent of free lunch eligible students scored at Level 1 in math in 2021, compared with 25 percent of students who are middle- to upper-income. Thirteen percent of free lunch students scored in Levels 3 and 4 compared with 36 percent of middle- and upper-income students.

Likewise, 29 percent of students without disabilities scored level 1, compared to 64 percent of special education students; and 31 percent of non-disabled students scored score in Levels 3 and 4, compared to just 10 percent of students with disabilities.

These trends become self-perpetuating. Students from low-income families and those with disabilities are less likely to attend and complete postsecondary programs, which means as adults they and their families are more likely to have lower incomes and experience unemployment and poverty. That means their children are more likely to have challenges in school.

School leaders can take steps to improve assessment results, graduation rates and postsecondary success rates.

State assessment scores began dropping in 2015 during eight years of cuts to education funding and trends worsened after COVID. However, this year a six-year phase-in to restore funding is complete and districts are receiving additional federal dollars to help recover from COVID.

The State Board of Education has made student academic preparation for postsecondary success, with a goal of 75 percent of students at Level 3 or 4 on state tests, along with graduation and postsecondary success the major outcomes for its Kansans Can vision and school accreditation process. That process begins with looking at each district’s data on student outcomes, planning to improve or maintain outcomes, executing those plans and looking at new outcomes to evaluate and adjust those plans. Student outcomes should be an important part of every school board meeting.

School leaders can take advantage of state and federal assistance to address their needs, such as teacher training to improve student reading skills, and using state and federal funding to implement evidence-based practices. They can compare their results to other districts and find out what is working in the most successful schools.

Schools can work to build stronger ties with parents on the importance of academics and postsecondary planning, and help students develop personalized plans to help them connect academic preparation to their interests and goals. That may mean finding ways to deliver instruction in ways that are more relevant to student needs.

All of these steps should help improve student success. But they are also tied to the State Board’s accreditation and school design system and to new legislation and oversight, such as linking state assessment results to school board’s process to adopt the budget; requirements for testing, intervention and parent communication in the new Every Child Reads Act; and upcoming audits of at-risk funding.

Public schools need to focus on state assessments not because they are a perfect measure of student achievement – they are not – but because they are an indicator of how well the system prepares students for success after they leave that system.

Additional settings for Safari Browser.

Additional settings for Safari Browser.